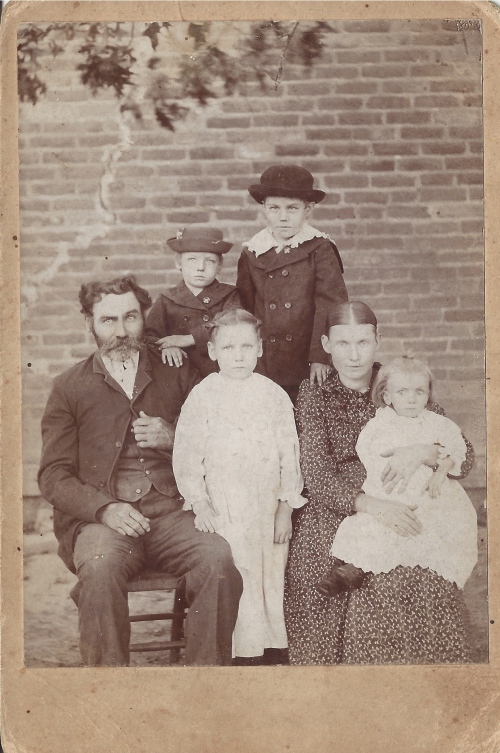

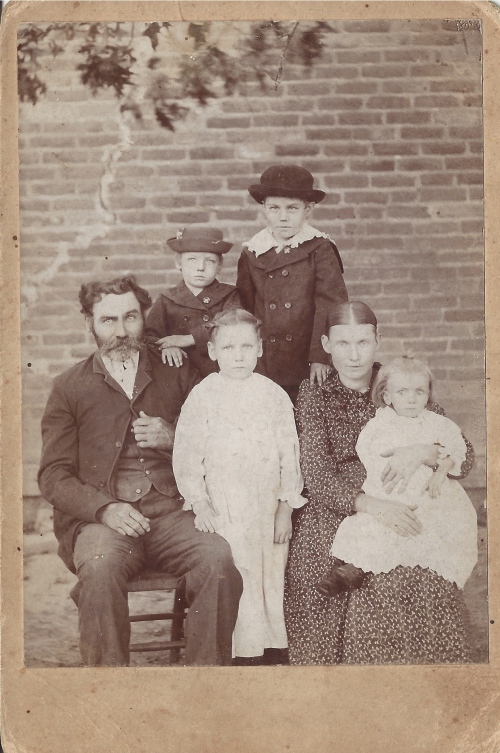

Mac and Alice Carson, in about 1896: Janie and Lonnie in front, Ross and James in back

I’ve a sheet of paper about 60 years old, which I had framed in an acid-free matte. I don’t display it, however, because I don’t want the sheet to yellow. The handwriting is my father’s (a big, intimidating truck-driver, he had pretty handwriting), and he records the family of his maternal grandparents, Wesley (“Mac”) and Alice Carson, including him and his sister Gladys. All of the information is in pencil, except for what I’ve placed in bold type, which is in blue pen. I assume thereby that he wrote out this information before 1953, although he doesn’t add Alice’s 1951 death. I’ve added “b.” and “d.” whereas Dad’s sheet has the columns “Name, Birth, Town, Death, Town” across the top.

Wesley McDonald Carson b. May 18, 1855 d. July 18, 1924 Vandalia

Mary Alice Colburn b. July 6, 1866 Married July 7, 1886

[Their children:]

Mary Alice b. April 17, 1887 Loami d. April 28, 1887 Loami

James Taylor b. August 6, 1888 Loami d. March 11, 1909 Vandalia

Permelia Jane b. March 22, 1890 Beecher City

Harry McDonald b. July 12, 1891 Beecher City d. August 6, 1892 Beecher City

Eldon Ross b. October 23, 1892 Beecher City d. June 11, 1953

Roland b. Sept.3, 1894 East of Ramsey d. Sept. 4, 1896 Ramsey

Lonnie b. Feb. 6, 1896 Ramsey

Lennie b. Feb. 6, 1896 Ramsey d. Feb. 8, 1896 Ramsey

Floyd b. Jan. 25, 1898 Ramsey d. Aug. 6, 1902 Vandalia

Millie Ellen b. Jan. 28, 1900 Vandalia

Lile b. Oct. 16, 1902 Vandalia d. Sept. 28, 1903 Vandalia

Lela Bella b. Feb. 8, 1904 Vandalia d. Feb. 3, 1956 Mich. Utica

Kitty Pauline b. June 28, 1906 Vandalia

Roy Wayne b. July 5, 1912 Vandalia

Andrew Christian Stroble, Permelia Jane Carson, married Dec. 27, 1908

Their children

Paul Edward b. July 21, 1912

Paul Edward Stroble and Mildred Abagail Crawford, married in St. Charles, Missouri, July 12, 1941

Mary Gladys b. May 17, 1914 married Paul Houck

Dad died in September 16, 1999. His sister Gladys, though, is still alive. [She died September 2, 2011, not long after I posted this.] To think she was born prior to the beginning of World War I! For geographical identification: Vandalia is my hometown, in Fayette County, Illinois. Ramsey is a few miles north of Vandalia (my grandfather Andy’s family are buried there). Beecher City is east of Ramsey, but in the northwest corner of Effingham County (and between Ramsey and Beecher City is the village of Herrick, near where Mac Carson’s father and grandfather are buried in the Lorton Cemetery). Loami, meanwhile, is in Sangamon County, near Springfield, where the Colburn family had settled.

I remember some of these people. My great-aunts Millie Ellen (“Peg”) and Pauline lived in Decatur, IL when I was little, and we’d visit them from time to time. I don’t remember visits to Pauline’s house as clearly, other than a general feeling of family love and warmth. Supposedly, while visiting Aunt Peg and her husband on one weekend when I was quite small, I tried to fold a live cat in half and put it into a toy dump truck—one of those stories you don’t remember about yourself but your relatives revisit it many times over the years, so that you’re perpetually a small child who did something funny.

I remember Uncle Lonnie more vaguely–I think he died in the late 1960s or early 1970s–but he came to our house a few times. Ross died prior to my birth but over the years I knew and enjoyed his family, including his widow Lydia (“Pidge,” as everyone called her) and several of their children and their children. Among his uncles and aunts Dad seemed close to Ross. But he loved his aunts, too, and was fond of his uncle Roy, whom you’ll notice is only sixteen days older than Dad. In other words, in 1912, my grandmother (aged 22) and her own mother (aged 46) were pregnant at the same time.

I remember my grandmother, who went by “Janie,” and who died in 1991 aged 101. She was only 45 when my grandfather Andy died in 1935. She remarried, but my dad was estranged from his stepfather, who was always referred to as “the goddamned bald-headed son of a bitch” and variations thereof. My mother selflessly did them many favors over the years and made sure I knew not only Mom’s mother, to whom I was very close, but “my other grandmother.” They gave Mom their 1963 Chevy which became my first car; I’ve told that story elsewhere in this blog.

My mother’s care of her mother-in-law–who could be hot-tempered and uncooperative–gave me a lifelong lesson in the goodness of caring for people whether they “deserve” care of not—and I’ve told Mom this. Her caring efforts were among my chief early influences.

The greater sadness of this list is apparent as you look at the dates, and you realize of course that six of Mac and Alice’s fourteen children died in infancy or young childhood. James died at age 21 from an accidental gunshot during a hunting trip—a tragedy even more haunting because Mac’s father also died young the same way, in 1859, and was also named James Carson. To think that Alice outlived seven of her fourteen children (not to mention her son-in-law, my grandfather Andy) is also so tragic, I have a hard time conceiving such a thing. I’d guess that the loss of one child is unspeakably horrible. I write this feeling despair.

Mac and Alice, and their oldest son James, are buried together in a pretty area of Vandalia’s South Hill Cemetery. If you enter the cemetery from Sixth Street, turn right along the military graves, and proceed straight south, the road forks and, to the left, provides a lovely view of the Kaskaskia River bottoms. I’ve a friend who wants her ashes scattered in this area. My family members are buried down the slope just as you turn left on that loop. I vaguely remember Mom, Grandma Janie, and me

Mac and Alice, and their oldest son James, are buried together in a pretty area of Vandalia’s South Hill Cemetery. If you enter the cemetery from Sixth Street, turn right along the military graves, and proceed straight south, the road forks and, to the left, provides a lovely view of the Kaskaskia River bottoms. I’ve a friend who wants her ashes scattered in this area. My family members are buried down the slope just as you turn left on that loop. I vaguely remember Mom, Grandma Janie, and me  visiting the graves with flowers in the springtime. Mac’s father and grandfather, James Carson (1819-1859) and John Carson (1794-1844) are also buried in sight of the river valleys. In the

visiting the graves with flowers in the springtime. Mac’s father and grandfather, James Carson (1819-1859) and John Carson (1794-1844) are also buried in sight of the river valleys. In the

“front” of the Lorton Cemetery, their graves are side by side, marked by stones that have sunk into the ground but are readable. I’ve a happy memory of a Sunday road trip with my dad, not

long before he died, as we visited that cemetery and then drove over to Ramsey to visit the graves of his Strobel grandparents.

******

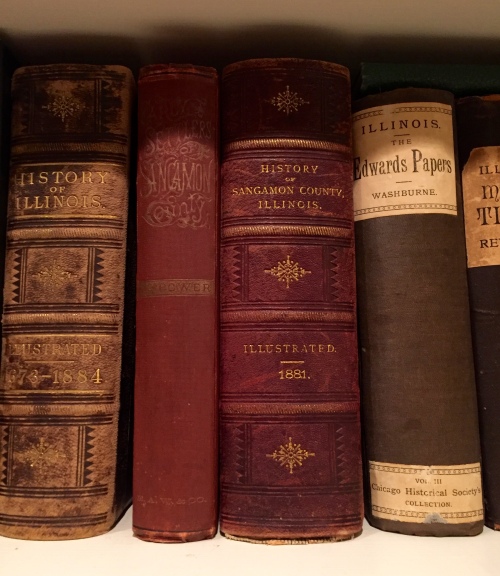

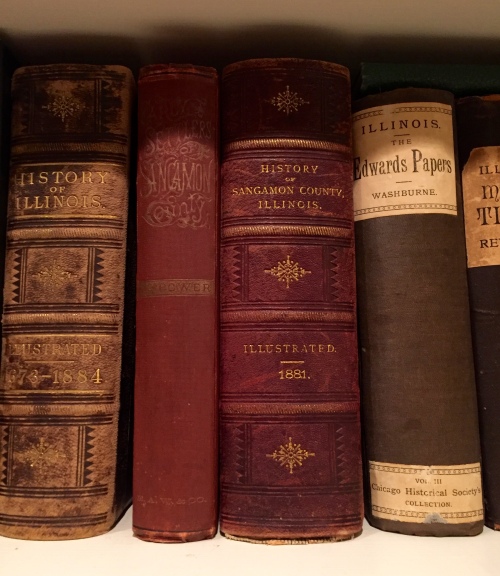

I think I’ll post a few 19th century accounts of the family, which Uncle Roy gave me forty years ago. He gave me copies from Past and Presnt of the City of Springfield and Sangamon County, vol. 2, by Joseph Wallace (Chicago, 1904), History of Sangamon County, Illinois (Chicago, 1881), and Early Setttlers of Sagamon County (1876).

Here is an excerpt from the 1881 history, page 938. Paul Colburn was my great-grandmother Alice’s great-grandfather. He and William and other relatives are buried in Loami, IL’s cemetery.

“Paul Colburn, one of the first permanent settlers of Loami, was born about 1761, in Hillsboro county, New Hampshire. He subsequently moved to Massachusetts, where hew as united in marriage with Mehitable Ball. In 1809, the family moved to Grafton county, new Hampshire, where they remained until September 1815; went from there to Ohio.

“In March, 1821, Paul Colburn, this daughter Isabel, William Colburn, wife and three children, the four orphan children of Isaac Colburn, and a Mr. Harris, started in a wagon drawn by four oxen for Morgan county. They traveled through rain, mud and unbridged streams for about five weeks, which brought them to the south side of Lick creek, on what is now Loami township, where they found an empty cabin. From sheer weariness, they decided to stop, and Mr. Harris, the owner of the wagon and oxen, went on to Morgan county.

Power’s “Early History” from 1876, and the 1881 history.

“Soon after their arrival, Wm. Colburn gave a rifle gun for a crop of corn just panted, and in that way began to provide food. He scoured a team and went after his brother Ebenezer, and brought him and his wife to the settlement, arriving in October, 1821.

“Having succeeded in bringing so many of his descendents to the new country, and witnessed their struggles to gain a foothold and provide themselves with homes, Paul Colburn died February 27, 1825, near the present town of Loami. The other members of the family lived for many years.”

Sangamon County was established by Illinois law on January 30, 1821, so the Colburns were among the first settlers of the area and very early settlers of the formally-designated Sangamon County.

The 1876 Early Settlers of Sangamon County gives an even more full account of Paul’s travels and hardships (p. 211).

William and Achsa Colburn’s grave in Loami, IL, with a plaque for William’s father Paul

“In 1809 the family moved to the vicinity of Hebron, Grafton county, N.H., where they remained until Sept. 1815, when Paul Colburn and his wife, his son Isaac with his wife and two children, his son William and his wife, they having been married but a few days, and his unmarried daughter, Isabel, started from Hebron in wagons to seek a new home in Ohio, at that time the ‘far west.’ On reaching Olean, at the Alleghany river, they found the river two low to bring all their goods on boards, as they had intended. They sold their wagons and teams, put the remaining good sand their families on a raft, and started down the river, reaching Pittsburg on the evening of December 24, 1815. ice was forming in the river, and they were compelled to stop there for the winter. While they were in Pittsburg, Paul Colburn was joined by his son Ebenezer, who had been serving in the United States army in the war with England, then just ended. In the spring of 1816, Isaac and Ebenezer went up the Alleghany river and made a raft of logs suitable for making shingles, and partially loaded it with hoop poles. They expected to have gone down the Ohio river in June, but the whole season was one of unusual low water, and December arrived before they reached Pittsburg with their raft. The whole party went down on the raft to Marietta, O., where they engaged in farming and other pursuits. Ebenezer was married in Marietta, and in the spring of 1820 Paul Colburn and his wife, Isaac and his family, and Ebenezer and his wife, embarked on a raft, leaving William to close up the business at Marietta. They landed their raft at Louisville, Ky., and left Isaac there to work up and sell their lumber. The other members of the family continued down the river to Shawneetown; Paul Colburn, his wife and daughter remained there. Ebenezer and his wife went on to join some relatives of her’s in Monroe County, Ill., about fifty miles south of St. Louis.

“In August of that year Isaac Colburn and his wife died at Louisville within days of each other, leaving six children among strangers, and on the first of November Mrs. Mehitibel Colburn died at Shawneetown. About the time of her death William Colburn embarked with his family on a boat at Marietta, floated down to Louisville, and took on board four of his brother Isaac’s children, one having died, and another been placed in a good home. He went to Shawneetown and joined his bereaved father and sister, arriving Dec. 24, 1820.

“In March, 1821, Paul Colburn, his daughter isabel, William Colburn, wife and three children, the four orphan children of Isaac Colburn, and a Mr. Harris, started in a wagon drawn by four oxen for Morgan county. They traveled through rain, mud and unbridged streams for about five weeks, which brought them to the south side of Lick creek on what is now Loami township, where they found an empty cabin. From sheer weariness they decided to stop, and Mr. Harris, the owner of the wagon and oxen, went on to Morgan county.

“Soon after their arrival Wm. Colburn gave a rifle gun for a crop of corn just planted, and in that way began to provide food. He secured a team and went after his brother Ebenezer, and brought him and his wife to the settlement, arriving in October, 1821.

“Having succeeded in bringing so many of his descendants to the new country, and witnessed their struggles to gain a foothold and provide themselves with homes, Paul Colburn died Feb. 27, 1825, near the present town of Loami.” The source then lists his children and their information.

That book also gives an account of William and Achsa Colburn:

“COLBURN, WILLIAN, brother to Issac, Abel and Ebenezer, was born June 3, 1793 at Sterling, Mass., married Aug. 15, 1815, at Hebron, N.H. to Achsa Phelps, whow as born at that place July 9, 1796. They came to Sangamon county, Ill., arriving April 5, 1821, in what is now Loami township. THey had three children before moving to Sangamon county, and even after, the youngest of whom died in infancy. [The text gives information about those children. Of those, my great-great-grandfather, John T., is indicated as

Two extant photos John T. Colburn, one with his wood carvings, the other taken as he worked.

being born November 23, 1840, married to Martha J. Beck, born April 9, 1845 at Loami. Two of their children, jaquetta and Lillie died in infancy, but Mary A.—my dad’s grandmother, discussed above—and Millie A. lived at home]… “William Colburn died June 10, 1869 at Loami, and Mrs. Achsa Colburn resides at Loami, on the same place settled by herself and husband, one year before the land was brought into market. William and his brother Ebenezer entered land together, and cultivated it for several years. About 1836 they built a steam saw and grist mill at the north side of Lick creek, and machinery for griding was soon added. it was the first mill of the kind within a radius of ten or twelve miles, and around that mill the village of Loami grew up. They continued in that business for many years, three mills having burned on the same spot. They were not always the owners, but their families were always connected with such enterprises. The sons of Wm. COlburn are now—1874—the owners of a mill within one hundred yards of where the first millw as built. one mill has burned where the new one stands. “The hardships endured by them and their families would be difficult to relate. Mrs. Achsa Colburn, now seventy-eight years old, has an unlimited fund of reminiscences connected with their advent into the county, and the difficulties of raising a large family. A loom was an indispensible article where all were dependent on the work of their own hands for the entire clothing of themselves and families. Mrs. Colburn tried all the men in the settlement, those of her own family included, in order to find some person who could make a loom, but all declined ot undertake it, some for want of skill, and all for want of tools. Mrs. C., then procured an axe, a hand saw, a drawing knife, and auger and a chisel, and went to work. She made her with her own hands a loom, warping bars, winding blades, temples for the lateral stretching of the cloth and for spools she used corn cobs with the pith pushed out. With these appliances she wove hundreds of yards of cloth, and made it up into garments for her family. This she did while caring for her family of fourteen children” (pp. 212-214).

Here is some information about the Carsons, from the 1881 History of Sangamon County:

“John Carson… was born in South Carolina, August 8, 1794. He was in the war of 1812, also in the Black Hawk War; he followed farming, and died November 19, 1844. [See him tombstone above.] His wife was Margery Parkerson, for in Carter county, Tennessee, October 19, 1799. She was a member of the Baptist Church, and mother of nine children; five are living—three boys and two girls. Mr. Carson has now two hundred and ninety-three acres of land, all under good cultivation, in Loami; he also has forty acres in Effingham county. He is a Democrat in politics, and cast his first vote for Frank Pierce in 1852. His father came to Illinois in 1814 and settled on Shoal creek, in Madison county” (p. 942).

And here is a little more, from Past and Present of Sangamon County (p. 1370):

“… John Carson, a native of South Carolina, was born in 1794 and was a son of James Starrett Carson, who was also born in South Carolina. The great-grandfather was John Starrett Carson, Sr., a representative of a family of Irish and Scotch

Lawn of Fayette Co. IL Courthouse. Thanks to my Facebook friend Gloria for taking this photo.

ancestry that was established in the south at an early period in the colonization of America. Six brothers of the name came to the United States prior to the Revolutionary war, establishing their homes in North and South Carolina. James S. Carson.. was a soldier of the Revolutionary war. He joined the army when but a bo and was in the battle of Kings Mountain, of Ramstard Mill and of Cowpens. Subsequently he removed to Tennessee, where he reared his family. [John Caron] spent his boyhood days in that state and became a soldier of the war of 1812. When his military service was over he found that his father had sold the farm in Tennessee and had removed to Illinois. John S. Carson then followed the family to this state and in 1818 established his home in Madison county. He was married there to Marjory Parson, whose birth occurred in Carter county, Tennessee. Soon afterward the young couple took up their abode upon a farm in Morgan county, Illinois, and about 1820 came to Sangamon county, when Mr. Carson purchased land which was then wild and unimproved, but which he developed into one of the productive farms of Woodside township.”

But James S. Carson eventually moved to Fayette County, Illnois, where I was born and raised. He is buried there in an unknown location, and he is honored on the monument to Revolutionary War soldiers buried in the county. The monument was dedicated on the grounds of the Fayette County Courthouse as part of the local Bicentennial celebrations in 1976.

*****

Altogether, here are the relationships of some of these forefathers and mothers to myself:

My dad was Paul Edward Stroble, 1912-1999

His parents were Andrew Christian Stroble (1882-1935) and Permelia Jane Carson Stroble (1890-1991), who later married Mike Plinke.

Jane’s parents were Wesley McDonald Carson (1855-1924) and Mary Alice Colburn (1866-1951), married July 7, 1886. I list their fourteen children above.

Mac Carson’s parents were James Carson (1819-1859) and Permelia Swanson. James Carson’s parents were John Carson (1794-1844) and Margery Parkinson (b. 1799). These two men’s tombstones are photographed above..

John Carson’s father was James S. Carson, and in turn his father was James Scarrett Carson Sr.

Then Alice Carson’s parents were: John T. Colburn (1840-1918) and Martha J. Beck (1845-1926). John T. Colburn’s parents were William Colburn (1793-1869) and Achsa Phelps (born 1796), and William’s parents were Paul Colburn (c. 1761-1825) and Mehetibel Ball (b. about 1757)

As a bit of happy serendipity: when I decided finally to update this essay (first posted three years ago), I realized it was the anniversary of Mac and Alice Carson’s marriage, July 7, 1886, 128 years ago today.

(For earlier family history, see my post: https://paulstroble.wordpress.com/2024/02/05/the-colburns-and-king-philips-war/ )

Read Full Post »